Nightmare In Hell! Battle for Iwo Jima

Military | Future Arms & Current News / World War 2

The Battle for Iwo Jima, February–March 1945

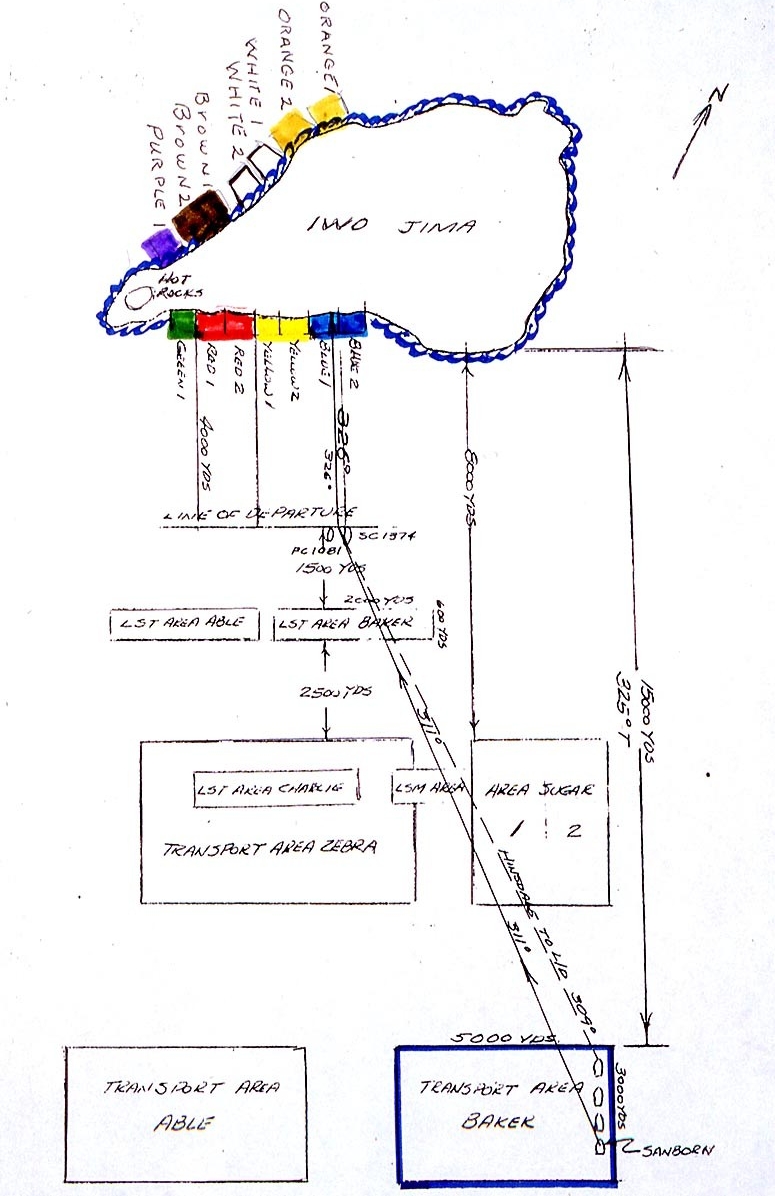

Diagram of the island’s invasion beaches, identified by the colors Green, Red, Yellow, and Blue. The alternate beaches on the other side of Iwo Jima are identified by Purple, Brown, White, and Orange. Also shown are the landing ship and transport areas offshore and the lines of approach used by boats from USS Sanborn (APA-93) to beaches Blue 1 and 2. Original 35mm transparency of a dragram probably prepared by the former Lieutenant Commander Howard W. Whalen, USNR, a boat group commander from Sanborn, after World War II. Note that the arrow pointing north actually points about 15 degrees west of north (NH 104377-KN).

The battleship USS New York firing its 14 in (360 mm) main guns on the island, 16 February 1945 (D minus 3)

Iwo Jima is a small volcanic island (eight square miles) located roughly midway between Saipan and Tokyo and, in 1945, was on the path of B-29 Superfortress missions flying from bases in the Marianas Islands to targets in Japan, which gave the island its strategic significance. The island is roughly triangular in shape (like a pork chop) and deceptively flat, with the 554-foot Mount Suribachi at the southwestern apex being the most prominent feature. The entire island is crisscrossed with caves, tunnels, and volcanic fissures, which the Japanese adapted for a very effective defense.

About 160 miles to the northeast of Iwo Jima are the somewhat larger islands of Hahajima and Chichijima (where future President George H. W. Bush was shot down and rescued on 2 September 1944). Although Chichijima had a better harbor (Iwo Jima only had a small man-made boat basin), the more rugged terrain of Chichijima was less suitable for rapid runway building. On 14 July 1944, Commanding General of the U.S. Army Air Forces, General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, recommended that Iwo Jima be taken for use as a base for fighters to escort the B-29 bombers to Japan and as an emergency divert field for damaged B-29s returning from missions over Japan. Another rationale was to keep the Japanese from using Iwo Jima to attack the B-29 bases in the Marianas. The Joint Staff planners agreed with this assessment, and the island was designated for capture on a “not to interfere” basis with other operations (at the time, the invasion of the Philippines). This resulted in delay, enabling the Japanese to continue fortifying the island. The invasion of Iwo Jima would be named Operation Detachment.

19 February 1945 air view of Marines landing on the beach

Although about 1,500 Japanese troops were lost on the way to Iwo Jima due to their ships being sunk by U.S. submarines, by the time of the U.S. landings in February 1945 there were about 21,000 Japanese troops on the island, most of them of the 109th Division of the Imperial Japanese Army under the command of General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, and about 2,000 Imperial Japanese Navy naval guard force troops under the command of Rear Admiral Toshinosuke Ichimaru. (Neither commander would survive the battle.) Defensive equipment included about 300 anti-aircraft guns, 33 naval guns of 4.7- and 6-inch size, 438 artillery pieces, 69 anti-tank guns, and 23 tanks.

The Japanese made very effective use of the island’s natural caves and tunnels, expanding them into an island-wide network. The island was honeycombed with pillboxes with mutually supporting fields of fire, often connected by interior tunnels. The larger artillery pieces were well camouflaged from the air and the sea, and protected by fortifications that were virtually invulnerable to anything except a direct hit. General Kuribayashi (who would prove to be one of the best Japanese army commanders the Americans ever faced) recognized that attempting to defeat any landing at water’s edge would almost certainly fail due to the effects of U.S. heavy naval gunfire. He used the naval guard force to man some beachfront defenses, but most of the troops and artillery were well inland, and initially hidden from view. A quote attributed to General Kuribayashi before the war was this: “The United States is last country in the world we should fight.” Nevertheless, he did his duty to the utmost.

LVTs approach Iwo Jima.

Kuribayashi’s strategy was to wait until the beaches were heavily congested with the initial assault waves, then open up with an extremely heavy artillery barrage, and then fight to the last man for every square foot of the island—inflicting the maximum number of casualties in doing so. Kuribayashi had no use for futile and wasteful banzai charges or premature seppuku (ritual suicide). Every soldier was expected fight for as long as possible until being killed. The nature of the volcanic sand on the beach was such that it was nearly impossible for troops to run, or to dig. A rock terrace made it extremely difficult for the Marines’ LVT(A) amphibious personnel carriers to get off the beach. The combined result of these factors would be sheer carnage for the U.S. Marine landing forces.

In early December 1944, the submarine Spearfish (SS-190), on her 12th war patrol, conducted an extensive photo reconnaissance of Iwo Jima, gaining considerable intelligence on the beaches and island operations. Nevertheless, Japanese camouflage and careful siting of guns to be invisible from seaward resulted in most Japanese artillery positions remaining unlocated. (On the same war patrol, Spearfish made the first submarine rescue during the war of ditched B-29 crewmen, picking up seven survivors of a B-29).

U.S. Navy and Marine Corps Organization for Iwo Jima

The invasion of Iwo Jima was under the overall command of Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz (promoted to five-star on 19 December 1944), the Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas. The operation would be conducted by about 450 ships of the U.S. Fifth Fleet, under the command of Admiral Raymond Spruance, embarked in heavy cruiser Indianapolis (CA-35). Spruance had relieved Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., on 26 January 1945, whereupon the Third Fleet was re-designated the Fifth Fleet (same ships, different fleet and task force/group/unit numbers. The Japanese already had this organization figured out by then). The landings would receive support from the Fast Carrier Task Force (TF 58), with Vice Admiral Marc “Pete” Mitscher, embarked on Bunker Hill (CV-17), resuming command from TF 38 Commander, Vice Admiral John S. McCain. TF 58 included a newly formed night-fighting Task Group (TG 58.5) consisting of the older carriers Saratoga (CV-3) and Enterprise (CV-6) equipped with specially trained night fighters and bombers.

The Joint Expeditionary Force (TF 51) was under the command of Vice Admiral Richmond K. “Kelly” Turner, with Marine Lieutenant General Holland M. “Howling Mad” Smith as the Commander Expeditionary Troops (TF 56). Both were veterans of multiple major amphibious operations. The main component of the landing force was V Amphibious Corps, commanded by Marine Major General Harry Schmidt, consisting of the 4th and 5th Marine Divisions, which would make the initial landings, and the 3rd Marine Division, which would follow up as necessary. In a new innovation, all aspects of pre-landing operations, bombardment, and air support would be under a single commander, Rear Admiral William H. P. “Spike” Blandy, Commander Amphibious Support Force (TF 52). The ships of the invasion force were under the command of Rear Admiral Harry W. Hill, Commander Attack Force (V Amphibious Force, TF 53). The force also included the Logistics Support Group under Rear Admiral Donald B. Beary, and a Search and Reconnaissance Group (TG 50.5).

Pre-Invasion Bombing and Bombardment

After the U.S. completed the capture of Saipan, Tinian, and Guam in the Marianas Islands in the summer of 1944, airfields for heavy bombers were quickly constructed by U.S. Navy Seabees and U.S. Army engineers. Heavy four-engine B-24 bombers commenced operations from Saipan in August 1944 to begin softening up Iwo Jima (the B-24 didn’t have the range to reach Japan from the Marianas) as U.S. intelligence reported that an extensive Japanese reinforcement of the island Jima was underway. The first B-24 mission to Iwo Jima took place on 10 August 1944, and virtually every day from then until the invasion, weather permitting, Iwo Jima was bombed.

The first B-29 Superfortress (which did have the range to reach Japan) arrived in 12 October 1944, and by the end of November 1944, enough B-29s were in the Marianas to conduct the first bombing mission (B-29s staging out of China had previously conducted bombing missions on southern Japan, but the logistics of flying the bombs and fuel (since there was no open road or port) over the Himalaya Mountains made such raids inefficient and largely ineffective. The first series of B-29 raids from the Marianas weren’t very effective either. Intended to be high-altitude precision bombing strikes against military and industrial targets, high winds and bad weather limited the success of the raids. It wasn’t until March 1945, when the B-29s switched to mass low-altitude nighttime fire-bombing raids on Japanese cities did they become effective, and a horrendous price was paid by the hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians who died as a result.)

After the first B-29 raid from Saipan on Japan on 24 November 1944, the Japanese quickly counterattacked with twin-engine bombers staging through Iwo Jima. The first two Japanese strikes were ineffective, but, on 27 November 1944, two Japanese bombers caught the B-29s as they were loading, destroying one and damaging another. Another strike a few hours later by 15 Japanese fighters destroyed three B-29s on the ground and badly damaged two others. Most of the Japanese aircraft in these strikes were lost. Japanese air strikes on Saipan, staged through Iwo Jima, continued intermittently until early January, ultimately destroying 11 B-29s and damaging 6 others. As the B-29s were hugely expensive and scarce strategic assets, this just added more impetus to the need to deprive the Japanese of the use of the airfields on Iwo Jima.

The first major U.S. response to the Japanese attacks from Iwo Jima took place on 8 December 1944, beginning with a fighter sweep by 28 P-38 long-range fighters, followed by 62 B-29s and 102 B-24s that plastered the island. However, due to overcast, the planes had to bomb by radar, which limited effectiveness. Coordinated with the airstrikes was a naval bombardment of the island by Cruiser Division (CRUDIV) 5, commanded by Rear Admiral Allan E. Smith, during which the heavy cruisers Chester (CA-27), Pensacola (CA-24), Salt Lake City (CA-25), and six destroyers shelled the island for 70 minutes (in broad daylight) with 1,500 8-inch and 5,334 5-inch rounds. Intelligence indicated that the Japanese airfields were ready for renewed operations within three days, although no additional Japanese air attacks occurred until Christmas. The day before Christmas, CRUDIV 5 plus five additional destroyers shelled Iwo Jima again. The Japanese were apparently unimpressed and, on Christmas Eve, launched a 25-plane strike on Saipan that destroyed one B-29 and damaged three others beyond repair.

The U.S. Navy heavy cruiser USS Pensacola (CA-24) underway at sea in September 1935.

On 27 December, CRUDIV 5 shelled Iwo Jima again and, on 5 January, as Army Air Forces aircraft bombed Iwo Jima, CRUDIV 5 shelled Hahajima and Chichijima. Destroyer Fanning (DD-385) destroyed Japanese LSV-102 (a Japanese version of an LST) in exchange for destroyer David W. Taylor (DD-551) suffering an underwater explosion, probably from a mine, that killed four crewmen and flooded the forward magazine. Although badly damaged, the ship was able to make it to safety under her own power. Finally, on 25 January 1945, augmented by the new battleship Indiana (BB-58) and under the overall command of Rear Admiral Oscar C. Badger II, CRUDIV 5 plus two additional destroyers bombarded Iwo Jima with 203 16-inch rounds and 1,354 8-inch rounds while driving off an attack by a lone Kate torpedo bomber, until deteriorating visibility curtailed the shelling.

First U.S. Carrier Aircraft Strike on Japan, 16–17 February 1945

USS Enterprise (CV-6)

As part of the plan to deceive the Japanese and cover the landings at Iwo Jima, the U.S. Fast Carrier Task Force (TF 58) conducted the first carrier strikes on the Japanese home islands on 16–17 February 1945. For months, Admiral Halsey had been itching to strike the Japanese home islands in late 1944, but the need to provide cover to the Leyte and then Lingayen landings in the Philippines resulted in repeated delays. As a result, Admiral Spruance and Admiral Mitscher executed the strikes.

Although the carrier Franklin (CV-13) and light carrier Monterey (CVL-26) (with future President Gerald Ford aboard) were temporarily knocked out by damage during Halsey’s foray into the South China Sea in January 1945 (which I will cover in a future H-gram), this loss was more than made up by the arrival of three new Essex-class fleet carriers, Bennington (CV-20), Randolph (CV-15), and Bunker Hill (CV-17). TF 58 included 11 large fleet carriers: nine Essex-class carriers, Saratoga (CV-3), Enterprise (CV-6), five Independence-class light carriers, eight fast battleships including the brand new Missouri (BB-63), the new battle-cruiser Alaska (CB-1), four heavy cruisers, ten light cruisers, and 77 destroyers. In reaction to the Japanese kamikaze tactics as well as the destruction of most of the Japanese fleet during the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the carrier air groups on the Essex-class carriers had been extensively reorganized and generally included a greatly increased number of fighters (about 73 F6F Hellcats and F4U Corsairs) and a reduced number of bombers (about 15 TBM Avenger torpedo bombers and 15 Helldiver dive-bombers).

On 10 February 1945, the Fast Carrier Task Force sortied from Ulithi Atoll en route Japan, utilizing extensive radio deception, the use of submarines to destroy Japanese picket boats, scouting by both U.S. Army Air Forces B-29 and U.S. Navy Liberator bombers, and a line of destroyers in advance of the carrier force, all intended to achieve surprise during the attack. The transit was also aided by foul weather that limited Japanese reconnaissance. TF 58 was organized as follows:

TG 58.1 Hornet (CV-12), Wasp (CV-18), Bennington (CV-20), Belleau Wood (CVL-24), Massachusetts (BB-59), Indiana (BB-58), Vincennes (CL-64), Miami (CL-89), San Juan (CL-54), and 15 destroyers, under the command of Rear Admiral Joseph J. “Jocko” Clark.

TG 58.2 Lexington (CV-16), Hancock (CV-19), San Jacinto (CVL-30), Wisconsin (BB-64), Missouri (BB-63), San Francisco (CA-38), Boston (CA-69), and 19 destroyers, under the command of Ralph Davison.

TG 58.3 Essex (CV-9), Bunker Hill (CV-17, Vice Admiral Mitscher embarked) Cowpens (CVL-25), South Dakota (BB-57), New Jersey (BB-62), Alaska (CB-1), Indianapolis (CA-35, Admiral Spruance embarked) PASADENA (CL-65), Wilkes Barre (CL-103), Astoria (CL-90), and 14 destroyers, under the command of Rear Admiral Frederick C. Sherman.

TG 58.4 Yorktown (CV-10), Randolph (CV-15), Langley (CVL-27), Cabot (CVL-28), Washington (BB-56), North Carolina (BB-55), Santa Fe (CL-60), Biloxi (CL-80), San Diego (CL-53), and 17 destroyers, under the command of Rear Admiral Arthur W. Radford (future Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1953–57).

TG 58.5 (Night Carrier Task Group) Enterprise (CV-6), Saratoga (CV-3), Baltimore (CA-68), Flint (CL-97), and 12 destroyers, under the command of Rear Admiral Matthias B. Gardner.

At 1900 on 15 February 1945, TF 58 commenced a high-speed run to arrive at a launch point at dawn on 16 February, 125 nautical miles southeast of Tokyo (and only 60 nautical miles off the coast of the main Japanese island of Honshu). Unfortunately, the bad weather that covered the approach and enabled TF 58 to arrive undetected also adversely affected the strikes. Nevertheless, fighter sweeps by hundreds of U.S. Navy carrier aircraft over the area around Tokyo Bay caught the Japanese almost entirely by surprise. There was almost no fighter opposition except to TG 58.2 (Davison) fighters over Chiba on the east side of Tokyo Bay, which were met by about 100 Japanese fighters, of which about 40 were shot down. The fifth fighter sweep (by TG 58.3 aircraft) flew directly over Tokyo, followed by bombing attacks against Japanese airframe and engine plants just before noon. Near the task force, destroyer Haynsworth (DD-700) sank three Japanese picket boats that had been missed by U.S. submarines. And, after dark, TG 58.5 flew a night-fighter sweep over the Tokyo Bay area.

On 17 February 1945, TG 58.5 (Enterprise and Saratoga) launched a pre-dawn strike, which was followed by bombing missions against industrial plants near Tokyo. However, the weather continued to deteriorate, forcing the planned afternoon strikes to be called off. Strikes against shipping near Tokyo were disappointing, mostly due to the weather, and only one significant cargo ship (the 10,600-ton Yamashiro Maru) was sunk. U.S. Navy aircraft claimed to have shot down 341 Japanese aircraft, with another 190 destroyed on the ground. U.S. losses were not insignificant, with 60 aircraft lost in combat (mostly due to anti-aircraft fire) and another 28 lost due to operational causes, out of 738 sorties that engaged enemy (out of 2,761 total sorties including combat air patrol).

As TF 58 was transiting from Japanese waters toward Iwo Jima on 17–18 February, destroyers Barton (DD-722), Ingraham (DD-694), and Moale (DD-693) sank three small Japanese picket boats. Destroyer Dortch (DD-670) encountered a fourth picket, a patrol craft armed with 3-inch guns that put up a spirited fight, hitting Dortch and causing 14 casualties, including three killed, before being rammed and cut in two by destroyer Waldron (DD-699). While TG 58.4 (Radford) conducted fighter sweeps and strikes on Chichijima and Hahajima, TG 58.2 (Davison) and TG 58.3 (Sherman) took up station west of Iwo Jima.

Explosions and smoke ashore on Iwo Jima, probably during the pre-landing bombardment, circa 19 February 1945. Note what appears to be a white phosphorus round bursting (center), and the boat operating close to shore (also in center). Original 35-mm Kodachrome transparency, photographed by the former Lieutenant Howard W. Whalen, USNR, boat group commander, USS Sanborn (APA-193) (NH 104337-KN).

Iwo Jima Landing Organization

Pre-landing operations at Iwo Jima were under the command of Rear Admiral “Spike” Blandy, Commander Amphibious Support Force (TF 52). (As Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance from 1941 to 1943, Blandy had a controversial role in the “Great Torpedo Scandal,” during which submarine skippers were blamed for defective U.S. torpedoes. On the other hand, he played a principal role in bringing the Bofors 40-mm and Oerlikon 20-mm anti-aircraft guns into the fleet (After the war, he would command Joint Task Force 1 for Operation Crossroads—the Bikini atom bomb tests—and would finish his career as the Commander-in-Chief U.S. Atlantic Fleet from 1947 to 1950).

A major component of the pre-landing operations was the Gunfire and Covering Force (TF 54) under Rear Admiral Bertram Rogers, which included six old battleships, four older heavy cruisers, one new light cruisers, and 16 destroyers. These included battleships Idaho (BB-42), Tennessee (BB-43), Nevada (BB-36), Texas (BB-35), Arkansas (BB-33), and New York (BB-34), heavy cruisers Chester (CA-27), Pensacola (CA-24), Salt Lake City (CA-25), and Tuscaloosa (CA-37), and light cruiser Vicksburg (CL-86). Nevada, Texas, Arkansas, and Tuscaloosa had participated in the D-Day landings in Normandy, the Battle of Cherbourg and Operation Dragoon (the invasion of Southern France), and along with New York transferred to the Pacific as U.S. naval surface operations against Germany wound down. The newer battleships North Carolina (BB-55) and Washington (BB-56) and the Fifth Fleet flagship, heavy cruiser Indianapolis (with Admiral Spruance embarked), joined the bombardment force on Iwo Jima D-day, 19 February 1945.

Although aircraft from TF 58 would conduct strikes on Iwo Jima, the great majority of air support to pre-landing strikes and subsequent support of Marines ashore was carried out by the ten escort carriers of Task Group 52.2 (Support Carrier Group), commanded by Rear Admiral Calvin T. Durgin. This force included;

Task Unit (TU) 52.2.1, under the command of Rear Admiral Clifton A. F. Sprague (Commander, Carrier Division 26), including escort carriers Natoma Bay (CVE-62, flagship), Wake Island (CVE-65), Petrof Bay (CVE-80), Sargent Bay (CVE-83), Steamer Bay (CVE-87), two destroyers, and four destroyer escorts. Wake Island embarked Composite Spotting Squadron One (VOC-1), a squadron that had received special training in airborne gunfire spotting (flying aircraft that were more survivable than the float planes catapulted off cruisers and battleships).

TU 52.2.2, under the command of Rear Admiral Durgin (Commander, Carrier Division 29), including escort carriers Makin Island (CVE-93, flagship), Lunga Point (CVE-94), and Bismarck Sea (CVE-95) and three destroyers.

TU 52.2.3, under the command of Rear Admiral G. R. Henderson (Commander, Carrier Division 25), included escort carriers Saginaw Bay (CVE-82), flagship), and Rudyerd Bay (CVE-81), and two destroyers and two destroyer escorts.

Two other escort carriers, Anzio (CVE-57) and Tulagi (CVE-72), operated independently, each with four destroyer escorts, on anti-submarine warfare duty, patterned after Atlantic hunter-killer groups. On 21 February, the old fleet carrier Saratoga (CV-3) would join the carrier support group after being detached from TF 58, and would form TU 52.2.4, under Captain L. A. Moebus, including the battlecruiser Alaska (CB-1) and three destroyers, for what would be a short-lived task unit.

TF 52 also included mine warfare craft, underwater demolition teams (UDT 12, 13, 14 and 15) aboard fast destroyer transports, an air-support control unit, and three groups of LCI(L) gunboats, mortar boats, and rocket support boats, under the command of Commander Michael J. Malanaphy (Commander LCI[G] Flotilla 3).

16 February (D-3)

On the evening of 15 February 1945, the lead units of TF 52 arrived off Iwo Jima and commenced bombardment operations at 0600 the next day, with minesweeping commencing at 0645. VOC-1 spotting aircraft flying from Wake Island made their Pacific debut and encountered very heavy Japanese anti-aircraft fire, suffering 20 aircraft damaged by flak and three shot down (almost the entire squadron damaged or lost, although most of the damaged aircraft made it back to the carrier and were repaired). In addition to heavy flak, gunfire spotting was marred by poor weather and a low ceiling. Later in the day, an OS2U Kingfisher floatplane spotting aircraft, launched from heavy cruiser Pensacola, was attacked by a Japanese “Zeke” (also known as “Zero”) fighter and, in a somewhat surprise development, Lieutenant (j.g.) D. W. Gandy not only survived, but managed to shoot down the Japanese fighter.

Planes from Makin Island attacked several luggers (small sailing vessels) filled with Japanese troops and, after missing with bombs and strafing, one plane managed to sink one with a direct hit by a drop tank. Aircraft attacking targets on Iwo Jima made extensive use of napalm (jellied gasoline), but encountered a very high rate of duds. During the day, as UDT-13 was setting up a light on Higashi Rock (off the coast of Iwo Jima), it came under Japanese fire, which was silenced by return fire from Pensacola and fast destroyer transport Barr (APD-39).

17 February (D-2), the Battle of the LCI Gunboats

On 17 February (D-2), the weather improved and visibility was good. Minesweeping continued, and Pensacola silenced some guns firing at the minesweepers. By 0700, the heavy bombardment ships (battleships and heavy cruisers) arrived off Iwo Jima and, at 0803, were ordered to close the beach. By 0911, battleships Idaho, Tennessee, and Nevada were only 3,000 yards off the shoreline. At 0935, a Japanese gun found the range on Pensacola and hit her six time in quick succession with 4.7-inch or 6-inch shells, wrecking her combat information center, setting fire to a float plane, puncturing the hull in several places, and killing 17 and wounding 98 crewmen. Pensacola withdrew, but only temporarily, before resuming her station and continuing to fire on Japanese targets during the day.

At 1025 on 17 February, the heavy bombardment ships were ordered to open distance to the beach in order to clear the way for four underwater demolition teams to conduct a close-in reconnaissance of the planned landing beaches along the southern side of the island. The fast destroyer transports Bull (APD-78, UDT-14 embarked), Bates (APD-47, UDT-12 embarked), Barr (APD-39, UDT-13 embarked), and Blessman (APD-48, UDT-15 embarked) dashed in and launched their LCP(L)s (landing craft, personnel, large, capable of carrying up to 36 personnel), which took the swimmers closer to the beach. Seven destroyers at the 3,000-yard line provided covering fire, while seven LCI(G) gunboats, under the command of Lieutenant Commander Willard Nash, USNR, embarked on LCI(G)-457, trailed behind the UDTs in line abreast, providing covering fire with their 40-mm and 20-mm guns. (LCI gunboats were typically armed with two 40-mm guns, four 20-mm guns, six .50-caliber machineguns, and ten Mark 7 4.5-inch rocket launchers.)

At about 1100, the LCI gunboats closed within 1,500 yards of the beach, preparing to unleash a barrage of 4.5-inch rockets, when Japanese positions along shore mistook the operation for the actual landing and prematurely opened fire. Small-arms and automatic-weapons fire was directed against the swimmers and mortar rounds began dropping around the LCI gunboats. A heavy casemated gun on Mount Suribachi joined in, followed by intense fire from a previously unlocated artillery battery north of the beaches.

The Japanese fire was very heavy, well-aimed, and effective, with the LCI gunboats bearing the brunt, as every one of them was hit repeatedly, in some cases with shells as large as 6-inch. Despite increasing damage and mounting casualties, the LCI gunboats refused to back down and continued to provide covering fire for the swimmers, but some of the Japanese guns were so well protected they could only be neutralized by direct hits. Eventually, the damage to several of the LCI gunboats became so severe that they temporarily withdrew to fight their fires and offload dead and wounded onto the fleet minelayer Terror (CM-5), which served as an impromptu casualty evacuation point and repair ship, enabling most of the LCI gunboats to get back in the fight.

Additional LCI gunboats of Flotilla 3, under the command of Commander Malanaphy (embarked on flotilla flagship LCI[FF]-627), dashed in to replace those that were temporarily forced out. Despite damage and casualties LCI gunboats 409, 438, 441, and 471 returned into the battle (409 despite 60 percent casualties). LCI(G)-474 was so badly damaged that she had to be abandoned; she was scuttled by gunfire from destroyer Capps (DD-550). In all, 12 LCI gunboats took part in the brutal fight, standing in until all but one of the UDT swimmers was recovered by 1240 (one of the recovered swimmers later died from his head wound).

During the LCI gunboat battle, the skipper of battleship Nevada, Captain H. L. “Pop” Grosskopf, turned a Nelsonian “blind eye” to the order to withdraw, eventually silencing the northern Japanese battery. (At the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801, British Admiral Lord Nelson, when informed of an order to withdraw, famously put his telescope to his blind eye and claimed he didn’t see the signal flag hoist, and went on to a great victory). At 1121, a Japanese shell hit the destroyer Leutze (DD-481) in her forward stack, killing seven and wounding 33 crewmen, including seriously wounding the skipper, Commander B. A. Robbins. Leutze remained in the fight, continuing to fire on Japanese positions to aid the LCI gunboats. Afterward, on the recommendation of Robbins, Lieutenant Leon Grabowsky was placed in command, thereby becoming the youngest (27 years, 4 months old) destroyer skipper in modern U.S. Navy history.

All 12 of the LCI gunboats were damaged during the UDT beach reconnaissance operation, with a total of 51 crewmen killed and 148 wounded. LCI(G-474 was lost and LCI(G)-441 and 473 would have to be towed away. All the LCI gunboats would be awarded Naval Unit Commendations. Commander Michael Malanaphy, Lieutenant Commander Willard Nash, and 11 of the LCI gunboat skippers would be awarded the Navy Cross.

The skipper of LCI(G)-449, Lieutenant (j.g.) Rufus Geddie Herring, USNR, (who had only recently relieved Lieutenant Commander Nash in command of the boat) would be awarded the first Medal of Honor of the Iwo Jima campaign;

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as Commanding Officer of LCI (G) 449 operating as a unit of LCI (G) Group Eight, during the pre-invasion attack on Iwo Jima on 17 February 1945. Boldly closing the strongly fortified shores under the devastating fire of Japanese coastal defense guns, Lieutenant (then Lieutenant Junior Grade) Herring directed shattering barrages of 40-mm and 20-mm gunfire against hostile beaches until struck down by the enemy’s savage counterfire which blasted the 449’s heavy guns and whipped her decks into sheets of flame. Regaining consciousness despite profuse bleeding he was again critically wounded when a Japanese mortar crashed the conning station, instantly killing or fatally wounding most of the officers and leaving the ship wallowing without navigational control. Upon recovering a second time, Lieutenant Herring resolutely climbed down to the pilot house and, fighting his own rapidly waning strength, took over the helm, established communication with the engine room and carried on valiantly until relief could be obtained. When no longer able to stand, he propped himself against empty shell cases and rallied his men to the aid of the wounded; he maintained position in the firing line with his 20-mm guns in action in the face of sustained enemy fire and conned his crippled ship to safety. His unwavering fortitude, aggressive perseverance and indomitable spirit against terrific odds reflect the highest credit upon Lieutenant Herring and uphold the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

(signed, Harry S. Truman)

A second UDT beach reconnaissance was planned for the afternoon, along the beaches on the northwest side of the island. By this point, none of the LCI gunboats were battle worthy, so the U.S. force adapted, and battleships Tennessee, Arkansas, Texas, and heavy cruiser Tuscaloosa provided cover for UDT mission. This time the Japanese mostly kept their heads down.

18 February (D-1), Bombardment and the First Japanese Air Attack

As a result of the LCI gunboat action on 17 February, a number of hidden Japanese defense positions had been revealed, and the bombardment plan on 18 February was changed accordingly. Battleships Tennessee and Idaho moved in to 2,500 yards and pulverized targets all day, reportedly causing more damage to Japanese defenses in one day than months of air bombardment. As General Kuribayashi had anticipated, the Japanese defenses along the beach were mostly destroyed, so the sacrifice of the LCI gunboats in exposing those defenses no doubt saved many lives in the initial landing. However, the bulk of Japanese artillery remained safely concealed, and the next day would kill so many Marines that any lives that might have been saved by the LCI gunboat action wouldn’t have been noticed. One of the controversies of the Iwo Jima landings was that the V Amphibious Corps commander, Marine Major General Harry Schmidt, had asked for ten days of naval bombardment and only got three. The reality is that without knowing precisely where the hidden Japanese batteries were, seven more days of shelling would have just churned up a lot of sand.

After the day-long, largely unopposed, bombardment of Iwo Jima on 18 February 1945, the Japanese mounted a small air attack after sunset. At 2121, a Japanese twin-engine bomber, identified as a “Betty,” attacked the fast destroyer transport Blessman (APD-48) and dropped two bombs. One hit the mess deck on the starboard side, just above the forward engine room, and the second bounced off the stack into the water. The ship lost all power and her Number 2 fire and engine rooms had to be abandoned due to heavy smoke, while fires raged in the mess, galley, and troop berthing. With all pumps knocked off line by shock, the crew resorted to bucket (and helmet) brigade to get the fires under control despite exploding anti-aircraft and small arms ammunition.

Blessman used a radio on one of her boats to call for assistance and destroyer transport Gilmer (APD-11—with Commander Draper Kauffman, chief staff officer, Commander Underwater Demolition Teams, embarked) responded. Initially, Gilmer stood off due to risk that Blessman would explode, and Kauffman took a small boat over to Blessman to evaluate the situation. The combined efforts of the two crews got the fires under control and Blessman was taken in tow to Saipan, where she was eventually repaired in time to participate in the occupation of Japan. However, 40 men were killed, including 15 members of UDT-15 (the largest loss of life by UDT during the war).

At 2130 on 18 February, the minesweeper Gamble (DM-15) was hit by two 250-pound bombs just above the waterline, flooding both firerooms and starting severe fires. Although five crewman were killed and nine wounded, her crew was able to get the fires and flooding under control well enough for her to be towed to Guam, where she was subsequently deemed to be unsalvageable, towed back to sea and sunk. (During the action on 17 February, a shell from Gamble had hit and detonated a large Japanese ammunition dump at the base of Mount Suribachi).

19 February 1945 (D-day)

The main body of Vice Admiral Richmond Turner’s Joint Expeditionary Force (TF 51) arrived off Iwo Jima before dawn on 19 February. The weather and seas were ideal, initially. At 0640, one minute before sunrise, the six battleships, five cruisers and numerous destroyers of TF 54 commenced the heaviest pre-H-hour bombardment of the war, and were joined by TF 58 battleships North Carolina, Washington, heavy cruiser Indianapolis (with Admiral Spruance embarked, who could never resist a shore bombardment), and the light cruisers Santa Fe and Biloxi. At 0645, Vice Admiral Turner gave the order to land the landing force, with H-hour set for 0900. The 5th Marine Division began disembarking from 22 transports and the 4th Marine Division began disembarking from 24 transports. LSTs approached the shore and floated out the first five assault waves of LVT amphibious vehicles.

At 0803, the bombardment was temporarily lifted to enable a large air strike by 120 TG 58.2 and TG 58.3 aircraft, which struck the island with strafing, rockets, bombs, and napalm. At 0825, the shore bombardment resumed with even greater intensity. At 0830, the first wave of 68 LVT(A) vehicles left the line of departure. At 0850, the bombardment was adjusted to allow seven minutes of strafing of the beaches by aircraft. Just before 0900, twelve LCS(L) rocket ships each fired a salvo of 120 4.5-inch rockets at the beach. At 0859, the battleship/cruiser bombardment was shifted 200 yards inland as the first wave of LVT(A)-4 tracked amphibious assault vehicles hit the beach almost precisely at 0900 (H-hour). At 0902, the barrage was shifted another 200 yards inland intended to be a rolling barrage ahead of the Marine advance. Initial Japanese opposition was negligible. Up to that point, everything had gone like clockwork. It wasn’t long afterward that everything went to hell.

At 0914, the skipper of VC-77 off escort carrier Rudyerd Bay, Lieutenant Commander Frank J. Peterson, with a 5th Marine Division observer aboard, was hit by ground fire and the Avenger exploded in a fireball visible to many. It was a bad omen.

The consistency of the sand on the beach bogged down everything, and the LVTs couldn’t get over a rock ledge. As successive waves of men, vehicles, and equipment piled up on the beach, just as Lieutenant General Kuribayshi had anticipated, the Japanese unleashed a horrific barrage of well-aimed artillery and mortar fire, killing hundreds of Marines and wounding many times that. Unable to run in the sand, or dig foxholes to protect themselves, the carnage was horrific, described as “every shell hole had at least one dead Marine,” and by a war correspondent as “a nightmare in hell.”

At 0955, four tank-carrying LSMs were hit and badly damaged by Japanese fire. Those tanks that got ashore bogged down or were disabled by mines, and many fell easy prey to Japanese anti-tank weapons and artillery fire. Navy personnel were caught in the barrage as well. Navy beach parties and shore fire-control parties assigned to each Marine battalion suffered high casualties, along with Navy corpsmen. Naval Construction Battalion personnel who landed with the Marine suffered high casualties as well, particularly since their initial duties required them to remain on the deadly beach clearing obstacles and laying mats so vehicles could get traction.

The 133rd Naval Construction Battalion, which landed with the 4th Marine Division on D-day, was especially hard hit and, during the course of the campaign, suffered 328 casualties (three officers and 39 enlisted killed and two missing) out of 1,100 men, the highest losses suffered by any battalion in the history of the Seabees. Many of these men were killed on the first day. The 31st Seabee Battalion landed with the 5th Marine Division on D-day and suffered significant casualties as well (although it was the 4th Marine sector at the northern end of the beaches that bore the brunt of Japanese fire). The 62nd Seabee Battalion landed a few days later and also took casualties.

At 1100, the wind suddenly veered and seas increased, causing many landing craft to broach, soon creating a scene like Omaha Beach at Normandy, where boats damaged by enemy fire or swamped by the sea littered the beachhead, making it difficult for follow-on echelons to find a place to land. Nevertheless, despite the high casualties, Marines began to move off the beaches toward the Japanese airfields inland, aided by continuing Navy fire from ships.

The battleship Nevada particularly distinguished herself in the eyes of the Marines, destroying multiple Japanese blockhouses, at times resorting to armor-piercing ammunition to do it (which normally wasn’t effective against sand and log bunkers, but worked better against concrete). At 1512, Nevada targeted a Japanese gun firing from a cave east of the beaches, firing two 14-inch rounds in direct-fire trajectory, scoring a direct hit that blew out the side of the cliff and the gun with it. In another example, LCS(L)-51 teamed up with the light cruiser Vicksburg; the LCS came within six hundred yards of the beach, firing tracer rounds at Japanese positions, which Vicksburg used to guide barrages of her rapid-fire 6-inch guns. Numerous similar examples exist, and historian Rear Admiral Samuel Eliot Morison assessed that naval gunfire support at Iwo Jima was the best of the entire war; casualties would have been far higher than they already were without it.

Nevertheless, despite 519 killed in action and another 47 who died of wounds on the first day, 30,000 U.S. Marines made it ashore that day from U.S. Navy ships. As night fell, the Marines awaited the expected mass banzai charge, and light cruiser Santa Fe stood by to provide illumination rounds. None came. In keeping with Kuribayashi’s plan to protract the fight and inflict as many casualties as possible, he would not waste men on futile and costly banzai charges. The result of his strategy was that a battle that was expected to take a few days stretched to over six weeks, at horrendous cost to the U.S. Marines, who had to root out Japanese positions one by one with grenades, flamethrowers, and satchel charges, often to find Japanese emerge in their rear from hidden tunnels.

Japanese Kamikaze Attack, 21 February 1945

With the exception of the air attacks on the evening of 18 February that badly damaged destroyer transport Blessman and minesweeper Gamble, Japanese air opposition to the Iwo Jima landings had been minimal, although battleship Missouri had shot down a Japanese plane on 19 February, her first aircraft kill of the war. The majority of U.S. aircraft losses around Iwo Jima continued to be the result of Japanese ground fire or due to operational causes, often the weather and low overcast. Also on 19 February, another task force of escort carriers arrived in the vicinity of Iwo Jima. This force was part of Task Group 50.8, the Logistics Support Group, consisting of escort carriers Bougainville (CVE-100), Admiralty Islands (CVE-99), Attu (CVE-102), and Windham Bay (CVE-92), delivering 254 replacement aircraft and 65 pilots for the Fast Carrier Task Force. Escort carriers Makassar Strait (CVE-91) and Shamrock Bay (CVE-84) provided air cover for the replacement aircraft group. Meanwhile, the escort carriers supporting the Marines received no replacements despite a steady attrition of combat and operational losses.

Due to bad weather on 20 February, a Japanese kamikaze mission against U.S. forces off Iwo Jima turned back. However, with improved weather on 21 February, the Japanese mounted their largest air operation against the U.S. force off Iwo Jima. At 0800, the “Mitate Unit No. 2,” a Special Attack (kamikaze) Unit under the command of Lieutenant Hiroshi Murakawa, took off from Katori Airfield near Yokosuka, Japan. The force consisted of 12 D4Y “Judy” dive-bombers and 8 B6N “Jill” torpedo bombers (half armed with bombs), escorted by 12 A6M “Zeke” fighters. The force staged and refueled at Hachijo-jima, which still left a flight of almost 600 miles to reach Iwo Jima. Two of the aircraft suffered mechanical failures and did not make it past Hachijo-jima, while another two were hit and damaged by TF 58 Hellcat fighters near Hachijo-jima and returned to the island (one of these would make a solo kamikaze attack on 1 March). The Japanese force was first detected by radar at a range of about 75 miles and was initially misidentified as “friendly” before it split in two. The first target was the carrier Saratoga (CV-3).

Kamikaze Strike on Saratoga

Saratoga had survived being hit twice by torpedoes from Japanese submarines. On 11 January 1942, she was hit by submarine I-16 off Hawaii and suffered six killed. However, she was damaged enough that she was not repaired in time to participate in the Battle of Midway that June. She was torpedoed again on 31 August 1942 by submarine I-26 south of Guadalcanal, suffering no deaths, but put out of action for another three months. Although she had a bit of a reputation as a hard-luck ship, she had fared better than her sister Lexington (CV-2), which had been sunk at the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942 with a loss of 216 of her crew.

Following operations in the Indian Ocean with the British Royal Navy in March–May 1944, Saratoga had been designated to serve as a training carrier along with Ranger (CV-4) for night carrier flight operations. However, the first “night carrier,” Independence (CVL-22), had proven too small for the mission. Saratoga was then called forward to TF 58 to operate with Enterprise (CV-6) and form Task Group 58.5 as the night-fighting task group, Night Carrier Division 7. (Despite early successes with nighttime flight operations, which almost always caught the Japanese by surprise, enthusiasm for these operations was pretty lukewarm, as they tended to disrupt the “battle rhythm” of the rest of the Task Force). In her new role, Saratoga embarked 53 Hellcat fighters and 17 radar-equipped Avenger torpedo bombers fitted out and trained for night fighting. Along with Enterprise, her aircraft conducted night-fighter sweeps and bombing missions during TF 58’s strikes on Japan during the night of 16–17 February 1945, raiding two Japanese airfields.

On 21 February, Saratoga, along with battlecruiser Alaska, was detached from TF 58 in order to provide additional air cover for ships supporting the amphibious operations on Iwo Jima. Enterprise remained with TF 58 to provide night-fighter cover. Unfortunately, by splitting TG 58.5, Saratoga would be short of escorts at a critical time. As the Japanese aircraft approached Saratoga, they made excellent use of the overcast and Saratoga fighters were only able to splash two.

At 1659, six Japanese aircraft burst out of the overcast. The first Japanese plane was downed by Saratoga’s gunners. The next two were hit, but skipped across the water, crashing into Saratoga’s side. Each of their bombs penetrated deep inside the ship before exploding, starting severe fires on the hangar deck. The fourth plane dropped a bomb that exploded on the anchor windlass, damaging the forward flight deck, and then flew on. The fifth plane crashed into the port catapult. The sixth plane smashed into an aircraft crane, scattering debris all over the flight deck as the flaming wing flew into the No. 1. gun gallery, wiping out all the personnel there. All of this occurred within the space of less than three minutes.

Despite the damage, Saratoga’s power plant remained unaffected and the crew was making good progress fighting the fires. The flight deck was unserviceable and aircraft in the air were directed to recover on the escort carriers. However, at 1846, near sunset, three kamikaze suddenly popped out of the overcast. Two were quickly shot down, but despite intense anti-aircraft fire from Alaska, one plane dropped its bomb before crashing into Saratoga’s flight deck. The plane itself bounced over the side causing little damage, but the bomb blew a 20-foot hole in the flight deck. Nevertheless, by 2015 Saratoga was capable of recovering aircraft although she could not launch any. The price had been steep: 123 dead and 192 wounded, with 36 of her aircraft destroyed.

Saratoga survived and was repaired, but finished her career as a training carrier, amassing 98,549 aircraft recoveries in 17 years of service, at the time a record. She met a somewhat ignominious end as a target for atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll in July and August 1946— it took two atom bombs to put her under.

Only yards from Iwo Jima’s landing beaches, Marines of the 5th Division make ready to land from a Coast Guard LCVP. The 5th Marine Division landed on beaches in close proximity to Mount Suribachi (NH 104225).

Loss of Bismarck Sea

The Japanese strike aircraft that split off continued farther south toward the U.S. escort carrier groups, which detected the incoming “bogeys” at 1653. The escort carriers quickly scrambled 65 fighters (FM-2 Wildcats) to intercept, but the combat air patrols could not find the Japanese in the clouds. At 1739, escort carrier Bismarck Sea launched still more fighters. At 1745, fighters off Saginaw Bay sighted a “Jill” torpedo bomber, but could not catch it before it crashed into either the net cargo ship Keokuk (AKN-4) or LST-447. Keokuk was hit and damaged by a “Jill” kamikaze just prior to sunset on 21 February 1945, with a loss of 17 killed and 44 wounded. LST-447 was also struck by a kamikaze on 21 February (although some accounts say 19 February), with nine killed and five wounded, as was LST-809, which apparently suffered no casualties.

By 1800, there were no signs of Japanese aircraft on radar and fighters aloft were cleared to recover, except one three-plane section of Wildcats from Makin Island. The Wildcats were vectored after a possible target at 1845, about 12 minutes after sunset, but saw nothing but Saratoga burning on the northern horizon. At this time, the escort carriers were in a circular air defense formation on course 040 degrees with five escort carriers arrayed around Saginaw Bay in the center. Lunga Point was furthest to the north, while Bismarck Sea was at the 072-degree position. With almost no warning, five or six “Jill” torpedo bombers came in from the northeast at high speed and low altitude. All ships in the formation opened fire as the enemy concentrated on Lunga Point.

At a range of 700 yards from Lunga Point, the first “Jill” dropped a torpedo before the plane was hit and destroyed by a 5-inch shell only 200 yards from the ship, while the torpedo missed between 50 and 100 yards ahead. The second “Jill” also dropped a torpedo that missed ahead of Lunga Point, while the plane crossed 15 feet over the aft end of the ship before disappearing into the darkness. The third plane was hit at point-blank range from Lunga Point and disintegrated. The fourth and last plane was hit and caught fire at about 1,000 yards from Lunga Point, but pressed on with the attack, dropping a torpedo at about 600 yards, which missed astern by only about 10–15 feet. The Japanese pilot aimed for the Lunga Point’s island, but the plane exploded just before impact. The fireball hit the aft end if the island, while the detached wing skidded across the flight deck in a spectacular streak of fire. However, this was extinguished in about three minutes, with only minor damage and minor personnel casualties thanks in part to the enforced use of new flash gear (which the crew disliked due to the heat, but which the captain insisted they wear at battle stations). By 0600 the next morning, Lunga Point was back in full operation.

As Bismarck Sea had recovered fighters after the previous scramble, her flight deck had become overcrowded with her own aircraft, along with a Saratoga fighter making a message drop, and two additional TBM Avenger torpedo bombers. As a result, Bismarck Sea had one F6F Hellcat, 19 FM-2 Wildcats, 15 TBM Avengers, and two OY-1s (a light observation aircraft) on board. In order to make deck space for the two extra Avengers, four Wildcats were struck below before they had been defueled, which would prove a fatal mistake.

Just after Bismarck Sea’s gunners stopped firing on the planes attacking Lunga Point, lookouts sighted an aircraft inbound, close aboard, only 25 feet off the water. The aircraft hit Bismarck Sea in the side abeam the after elevator, and the plane’s engine continued into the elevator well, severing elevator cables. The elevator, which had been on its way up, fell back into the hangar bay with a force that knocked torpedoes loose from the storage racks, causing them to roll about the deck. Bismarck Sea lost steering control, and fires broke out as the after sprinkler system and water curtain were knocked off line. Nevertheless, the crew ran hoses from the forward part of the ship and were bringing the fires under control, when, two minutes later, a second kamikaze struck the ship from near vertical.

The second aircraft dove through the flight deck just ahead of the flaming after elevator and impacted right in the middle of the four still-fueled Wildcats. This resulted in a massive blast that blew out the rear of the hangar, sending many crewmen overboard, killing most of the firefighters, and most of Repair Party 3, which was one deck directly below the explosion. The fires quickly became uncontrollable, and 40-mm and 20-mm ammunition began cooking off. The aft end of the ship became a raging conflagration.

At 1900, Captain John L. Pratt ordered the crew to abandon ship stations and, at 1905, gave the order to abandon ship. Before many of the crew could get over the side, an immense explosion, probably caused by detonating torpedoes, blew off the after flight deck and both sides of the after hangar. The ship began to list, but despite the catastrophic damage she remained afloat for more than another hour. At 2007, the Bismarck Sea listed sharply to starboard and the island broke loose before she went down stern first at 2012. A Japanese plane strafed survivors in the water.

At least 125 of Bismarck Sea’s crew were lost in the initial explosions and fire, and another 100 as the ship exploded and then sank. A further 100 were lost due to drowning and hypothermia while awaiting rescue in the cool water. Three destroyers and three destroyer escorts succeeded in rescuing 625 crewmen, but 318 were lost. All 37 of the aircraft aboard Bismarck Sea were lost.

The sinking caused flashbacks in the crew of Anzio, which was standing by Bismarck Sea and had been a witness to the loss of escort carrier Liscombe Bay off Makin Island in November 1943 with over 600 of her crew. Thus, Anzio witnessed the first and last U.S. escort carrier lost in the Pacific War. Bismarck Sea was the last U.S. Navy aircraft carrier ever lost.

Later that evening, jittery gunners on the escort carriers fired on Saratoga aircraft that were still searching for a place to land in the dark, forcing one to ditch in the ocean. Enterprise subsequently relieved Saratoga in working with the escort carriers and thereby earned two additional nicknames (aside from “Big E”): “Enterprise Bay,” as so many other escort carriers were named after bays, and “Queen of the Jeeps,” as escort carriers were often referred to somewhat disparagingly as “jeep carriers.”

By the first week of March, operations by the escort carriers tapered off, although fierce fighting continued ashore on Iwo Jima until the end of March. In an unusual mission, Avengers off Makin Island flew DDT insecticide-spraying missions over the island on 28 February and 4 March to counter the plague of flies resulting from so many unburied bodies. On 4 March, the first B-29 made an emergency landing on Iwo Jima and, on 6 March, the first U.S. Army Air Forces fighters flew into the airfields made ready by U.S. Navy Seabees. During the Iwo Jima operation, aircraft from the escort carriers flew 8,000 sorties, dropped 400 tons of bombs and 150 napalm tanks, and fired over 9,000 rockets, at a cost of 83 aircraft (including those that went down on Bismarck Sea) to both combat and operational causes.

Japanese Submarine Kaiten Missions

On 21 February 1945, three Japanese submarines departed Hikari, Japan. I-368, I-370, and I-44 each were piggybacking five Kaiten manned suicide torpedoes. Known as the “Chihaya group,” this was the third Kaiten operation launched by the Japanese. Their objective was to sink U.S. ships off Iwo Jima.

On 25 February 1944, I-44 was detected on surface by U.S. destroyers and destroyer escorts as she was re-charging her batteries. The submarine submerged and was pursued and kept down for 47 hours, during which CO2 levels in the sub exceeded 6 percent, on the verge of suffocating the crew before contact was lost. I-44 got underway again on 28 February, but was detected by an Avenger and broke off the attack. I-44’s skipper was subsequently relieved of command by Vice Admiral Shigeyoshi Miwa, commander of the Sixth Fleet (Japanese submarine force), who viewed I-44’s actions as insufficiently aggressive. (Miwa had assumed command of Sixth Fleet in July 1944 after Vice Admiral Takeo Takagi was trapped on Saipan during the U.S. landings and disappeared, presumably killed in action or a suicide with body never found.)

After sunset on 25 February, destroyer Bennion (DD-662) gained sonar contact on a Japanese submarine. Escort carrier Anzio (CVE-57) launched a radar-equipped Avenger, and then another, which at 0220 picked up a radar contact. The Avenger sighted the phosphorescent signature of a submarine that had just submerged and dropped a Mark 24 “Fido” acoustic homing torpedo and a pair of sonobuoys. In the morning, a large oil slick was seen to cover the area. Japanese submarine RO-43 was lost with all 79 of her crew, and was the first Japanese submarine lost off Iwo Jima. She was not part of the Chihaya Kaiten group. (At the time, the Mark 24 was referred to as a “mine” since the fact that it was actually an acoustic homing torpedo was a closely guarded secret. Mark 24s sank 31 German and six Japanese submarines during the war with an 18 percent kill effectiveness, compared to 9.5 percent for depth charges).

At 0304 on 26 February 1945, I-368 was detected on the surface by radar on an Avenger off the escort carrier Anzio about 35 nautical miles west of Iwo Jima. On the first pass, the Avenger overshot the submarine before circling back and dropping a float light and two sonobuoys. At 0338, I-368’s conning tower briefly broke the surface near the float light. The Avenger dropped a Mark 24, which may have hit the submarine. A second Avenger joined in and, after monitoring the sonobuoys, dropped another Fido, resulting in bubbles and an oil slick. At the time, there was no conclusive proof the submarine had been sunk, but Japanese records after the war confirmed that I-368 was lost with all 86 hands along with the five Kaiten and their pilots.

Soon after sunrise on 26 February 1945, I-370 surfaced with the intent to launch all five Kaiten at a group of nine U.S. transports (that happened to be empty and were leaving Iwo Jima). I-370 was quickly detected on radar from destroyer escort USS Finnegan (DE-307), Lieutenant Commander H. Huffman commanding. Upon being spotted, I-370 then crash-dived. At 0659, Finnegan gained sonar contact on I-370. Finnegan’s first hedgehog attack missed. She then dropped 13 depth charges set for deep attack, with no result. Continuing to search for the sub, Finnegan regained contact around 1000, conducted another hedgehog attack, and dropped 13 more depth charges at medium depth setting. This time there was a deep underwater rumble, followed by many bubbles and an oil slick. I-370 was lost with all 79 crewmen and all five Kaiten pilots and their submersibles.

More details. 37mm Gun fires against cave positions at Iwo Jima

On 1 March 1945, the Japanese commenced the fourth Kaiten mission, when the “Shimbu” group departed Japanese waters. I-58 and I-36 each piggy-backed four Kaiten suicide torpedoes. I-58 was spotted and forced to dive several times on 3 March and 4 March by aircraft from escort carriers Anzio and Tulagi (CVE-72). I-58 finally arrived off Iwo Jima on 7 March and prepared to launch her Kaiten the next morning, but received a recall order before doing so. On 9 March, I-58 received orders to participate in Operation Tan 2, a kamikaze raid on Ulithi Atoll, the major U.S. fleet anchorage in the Western Pacific at the time. (I will cover the raid in the next H-gram.) I-58 would sink the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis (CA-35) with a conventional torpedo attack on the night of 30 July 1945, after Indianapolis had delivered the components of the first atomic bomb to Tinian in the Marianas Islands. I-36 had not yet reached the vicinity of Iwo Jima by the time she received the recall order.

The Land Battle for Iwo Jima, 19 February–26 March 1945

Marine Lieutenant General Holland Smith stated, “Iwo Jima was the most savage and costly fight in the history of the Marine Corps.” Admiral Chester Nimitz’s quote that, “uncommon valor was a common virtue,” would be immortalized, with the virtue of being entirely true. However, an earlier quote by Admiral Nimitz, “This will be easy. The Japanese will give up Iwo Jima without a fight,” won’t be found in the USNA “Reef Points” section of quotes to be memorized by midshipmen. Marines would earn 22 Medals of Honor at Iwo Jima (about a quarter of the 82 awarded during the entire war). Navy personnel, including four Navy Corpsmen serving with the Marines, would be awarded five Medals of Honor, two of them posthumously. Just under 6,000 Marines died on the island, and another 17,272 were wounded (19,920 including those incapacitated by combat fatigue). This was the only time in the U.S. offensive in the Pacific War that U.S. casualties (dead and wounded) exceeded those of the Japanese (almost all dead).

The event that most remember from the Battle for Iwo Jima was the flag raising on Mount Suribachi on 23 February, immortalized in a photo by Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal, which was later turned into a bronze statue for the U.S. Marine Corps Memorial overlooking Washington, DC. This photograph was possibly the most famous of the entire war, and arguably one of the most famous of all time. Although the flag raising was a huge morale-booster to everyone who saw it (including Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, who came ashore on Iwo Jima that day), many weeks of hard fighting still remained ahead, including rooting out Japanese still hidden and fighting in caves and tunnels in Suribachi itself.

The flag raising captured in Rosenthal’s photo was actually the second of the day. On the morning of 23 February 1945, First Lieutenant Harold G. Schrier, USMC, volunteered to lead a 40-man combat patrol to the top of Mount Suribachi, bringing a flag taken from the battalion’s transport ship, Missoula (APA-211). The patrol made it to the top with little resistance, as ships were bombarding the Japanese at the time. The flag was attached to an iron water pipe and was raised, provoking a huge cheer from Marines on the island and loud blasts of ships’ horns, which tipped off the Japanese that something was up and caused the patrol to come under Japanese fire, which fortunately was quickly eliminated. Schrier would later be awarded a Navy Cross for leading the patrol.

Secretary of the Navy Forrestal’s boat touched shore just as the first flag went up, and Forrestal said to Lieutenant General Holland Smith, “Holland, the raising of that flag on Suribachi means a Marine Corps for the next five hundred years.” Forrestal then indicated he wanted the flag as a souvenir. This went over like a lead balloon with Schrier’s superior, Lieutenant Colonel Chandler Johnson, the 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines commander, who said “To hell with that!” when informed of Forrestal’s desire. Johnson ordered Lieutenant Albert “Ted” Tuttle, USMC, to go find a replacement flag, “and make it a bigger one.” According to the official U.S. Marine Corps history, Tuttle obtained a larger 96-by-56-inch flag from Ensign Alan Wood of the USS LST-779 (which would also be the last ship to cross paths with the USS Indianapolis before she was sunk just before the war ended). The flag had been sewn by Mabel Sauvageau, who worked in the flag loft of the Mare Island Naval Shipyard. (There is an alternative version that the flag came from U.S. Coast Guard Quartermaster Robert Resnick aboard LST-758, although this story did not surface until 1971.)

Five Marines took the bigger flag up Mount Suribachi, arriving around noon. Rosenthal and two Marine photographers reached the summit as the bigger flag was being attached to on old Japanese water pipe. Rosenthal almost missed the shot when the Marines raised the flag with no fanfare. It would turn out that identity of the six men in the photograph of the second flag raising would provoke controversy for years. Rosenthal would also be accused of “staging” the photograph, although that is not true.

Of the six men in the photo, three were killed later in the battle for Iwo Jima, one possibly by a shell from a U.S. Navy destroyer. One of those who died was initially misidentified as another Marine who died on Iwo Jima (both had helped with the flag raising, but only one was in the photo). This was corrected in 1947. Of the three who survived the battle, two of them were misidentified. One of those originally identified as being in the photo was Navy Hospital Corpsman John Henry “Doc” Bradley, who would be awarded a Navy Cross for heroism for his actions to save wounded Marines under intense fire on 21 February, two days before the flag raising. Bradley’s “battle buddy,” Ralph “Iggy” Ignatowski had been captured, brutally tortured, and executed by the Japanese in that same action, and Bradley had found his body, something which haunted him the rest of his life.

On orders of President Roosevelt, the three survivors were brought back to the States to participate in a war bond drive, which was wildly successful, raising $26.3 billion, twice the goal. However, of the three “survivors,” only one was actually in the Rosenthal photograph, Ira Hayes (a Native American, who tragically suffered from acute alcoholism and died of exposure and alcohol poisoning on a mountain in 1955). In 2016, after painstaking analysis (in part due to agitation by outside researchers), the Marine Corps announced that the man in the photo originally identified as Navy Corpsman Bradley was actually a Marine, Harold Schultz. Bradley assisted both flag raisings by piling rocks and staking down ropes to hold the poles in place after they were raised, but was not one of the six in the Rosenthal photograph, a fact he never revealed before his death. After yet more analysis, the Marine Corps announced in 2019 that the Marine originally identified as Rene Gagnon was actually Harold Keller (Keller’s wedding ring was the key piece of evidence). Gagnon, who survived and participated in the war bond drive, carried the second flag up Mount Suribachi, but was not in the Rosenthal photograph. Like many of those of that generation, neither Keller nor Shultz spoke up before their deaths about being in the most famous photo in Marine Corps history. In my book, however, every one of these men is a hero.

One of the announced ten Japanese prisoners (there were actually 216 Japanese POWs) taken on Iwo Jima is brought back to the beachhead by 3rd Division Marines toward the end of the struggle for the island, March 1945 (NH 104571).

I will not go into detail on the land battle, as this H-gram focuses on U.S. Navy operations, so I will just cite one Navy Cross citation as a representative example, to Marine Corps Private First Class Robert Ortiz, who was my dad’s cousin:

Interments of the 4th Marine Division.

The President of the United States takes pride in presenting the NAVY CROSS posthumously to

PRIVATE First CLASS ROBERT M. ORTIZ, UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS,

For service as set forth in the following CITATION

For extremely meritorious heroism while serving as an Automatic Rifleman in a platoon of Company F, Second Battalion, Twenty-fifth Marines, Fourth Marine Division, during action against enemy Japanese forces on Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands, from 19 February to 1 March 1945. Despite lack of previous experience as a flame thrower, Private First Class Ortiz repeatedly volunteered his services when two flame thrower operators became casualties. Joining whichever platoon was engaged in the assault, he voluntarily carried his weapon many times through murderous enemy machine-gun, sniper and rifle fire to positions fifty to one hundred yards in front of the lines, steadfastly refusing relief from this extremely hazardous and tiring duty until he had aided in the destruction of ten Japanese pillboxes. On 1 March, courageously attempting to extricate his company from a heavy barrage of fire from an enemy fortified emplacement, after a demolition team had failed to get close enough to destroy this position, he crawled with his flame thrower to an exposed but advantageous firing point and, by diverting the hostile fire from the demolition team, enabled it to contact and destroy the hostile group. Mortally wounded during this action, Private First Class Ortiz, by his aggressiveness and indomitable fighting spirit, contributed materially to the successful accomplishment of his company’s mission. His courageous devotion to duty was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.

(For the president, James Forrestal, Secretary of the Navy)

The Medal of Honor citations for the four Navy Corpsmen also provide a representative example of the valor and sacrifice of those who fought on Iwo Jima:

28 February 1945—Pharmacist’s Mate First Class John H. Willis (posthumous)

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as Platoon Corpsman serving with the 3rd Battalion, 27th Marines, 5th Marine Division, during operations against enemy Japanese forces on Iwo Jima, Volcano Islands, 28 February 1945. Constantly imperiled by artillery and mortar fire from strong and mutually supporting pillboxes and caves studding Hill 362 in the enemy’s cross-island defenses, Willis resolutely administered first aid to the many Marines wounded during the furious close-in fighting until he himself was struck by shrapnel and was ordered back to the battle-aid station. Without waiting for official medical release, he quickly returned to his company and, during a savage hand-to-hand enemy counterattack, daringly advanced to the extreme front lines under mortar and sniper fire to aid a Marine lying wounded in a shell-hole. Completely unmindful of his own danger as the Japanese intensified their attack, Willis calmly continued to administer blood plasma to his patient, promptly returning the first hostile grenade which landed in his shell-hole while he was working and hurling back 7 more in quick succession until the ninth exploded in his hand and instantly killed him. By his great personal valor in saving others at the sacrifice of his own life, he inspired his companions, although terrifically outnumbered, to launch a fiercely determined attack and repulse the enemy force. His exceptional fortitude and courage in the performance of duty reflect the highest credit upon Willis and the U.S. Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.

(signed, Harry S. Truman)

The destroyer escort USS John Willis (DE-1027), in commission from 1957 to 1972, was named in his honor.

3 March 1945—Pharmacist’s Mate Third Class Jack Williams (posthumous)

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving with 3rd Battalion, 28th Marines, 5th Marine Division, during the occupation of Iwo Jima Volcano Islands, March 3, 1945. Gallantly going forward on the front lines under intense enemy small-arms fire to assist a Marine wounded in a fierce grenade battle, Williams dragged the man to a shallow depression and was administering first aid when struck in the abdomen and groin three times by hostile rifle fire. Momentarily stunned, he quickly recovered and completed his ministration before applying battle dressing to his own multiple wounds. Unmindful of his own urgent need for medical attention, he remained in the perilous fire-swept area to care for another Marine casualty. Heroically completing his task despite pain and profuse bleeding, he then endeavored to make his way to the rear in search of adequate aid for himself when struck down by a Japanese sniper bullet which caused his collapse. Succumbing later as a result of his self-sacrificing service to others, Williams, by his courageous determination, unwavering fortitude and valiant performance of duty, served as an inspiring example of heroism, in keeping with the highest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.

(signed, Harry S. Truman)

The guided missile frigate USS Jack Williams (FFG-24) was named in his honor, serving in commission from 1981 to 1996.

3 March 1945—Hospital Corpsman Second Class George E. Wahlen, USNR

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving with the 2nd Battalion, 26th Marines, 5th Marine Division, during actions against Japanese forces on Iwo Jima in the Volcano Group on 3 March 1945. Painfully wounded in the bitter action on 26 February, Wahlen remained on the battlefield, advancing well forward of the frontlines to aid a wounded Marine and carrying him back to safety despite a terrific concentration of fire. Tireless in his ministrations, he consistently disregarded all danger to attend his fighting comrades as they fell under a devastating rain of shrapnel and bullets, and rendered prompt assistance to various elements of his combat group as required. When an adjacent platoon suffered heavy casualties, he defied the continuous pounding of heavy mortars and deadly fires to care for the wounded, working rapidly in an areas swept by constant firing and treating 14 casualties before returning to his own platoon. Wounded again on 2 March, he gallantly refused evacuation, moving out with his company the following day in a furious assault across 600 yards of open terrain and repeatedly rendering aid while exposed to the blasting fury of Japanese guns. Stout-hearted and indomitable, he persevered in his determined efforts as his unit waged a fierce battle and, unable to walk after sustaining a third agonizing wound, resolutely crawled 50 yards to administer first aid to still another fallen fighter. By his dauntless fortitude and valor, Wahlen served as a constant inspiration and contributed vitally to the high morale of his company during critical phases of the strategically important engagement. His heroic spirit of self-sacrifice in the face of overwhelming enemy fire upheld the highest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service.”

(signed, Harry S Truman)

After the war, Wahlen gained a commission in the U.S. Army, serving in combat in Korea and Vietnam (Purple Heart) before retiring in 1968.

15 and 16 March 1945—Pharmacist’s Mate First Class Francis J. Pierce

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while attached to 2nd Battalion, 24th Marines, 4th Marine Division, during the Iwo Jima campaign, 15 and 16 March 1945. Almost continuously under fire while carrying out the most dangerous volunteer assignments, Pierce gained valuable knowledge of the terrain and disposition of troops. Caught in heavy enemy rifle and machinegun fire which wounded a corpsman and 2 of the 8 stretcher bearers who were carrying 2 wounded Marines to a forward aid station on 15 March, Pierce quickly took charge of the party, carried the newly wounded men to a sheltered position, and rendered first aid. After directing the evacuation of 3 of the casualties, he stood in the open to draw the enemy’s fire, with his weapon blasting, enabling the litter bearers to reach cover. Turning his attention to the other 2 casualties, he was attempting to stop the profuse bleeding of one man when a Japanese fired from a cave less than 20 yards away and wounded his patient again. Risking his own life to save his patient, Pierce deliberately exposed himself to draw the attacker from the cave and destroyed him with the last of his ammunition. Then, lifting the wounded man on his back, he advanced unarmed through deadly rifle fire across 200 feet of open terrain. Despite exhaustion and in the face of warnings against such a suicidal mission, he again traversed the same fire-swept path to rescue the remaining Marine. On the following morning, he led a combat patrol to the sniper nest and, while aiding a stricken Marine, was seriously wounded. Refusing aid for himself, he directed treatment for the casualty, at the same time maintaining protective fire for his comrades. Completely fearless, completely devoted to the care of his patients, Pierce inspired the entire battalion. His valor in the face of extreme peril sustains and enhances the finest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service.

(signed, Harry S Truman)

Pierce was originally awarded a Navy Cross and a Silver Star, which were subsequently combined and replaced by the Medal of Honor.

The debate over whether Iwo Jima was “worth it” began almost as soon as the first news reports reached the American public, many of whom were appalled by the staggering cost the U.S. Marine Corps had paid for a small rock in the middle of nowhere. The issue is an interesting academic exercise in hindsight, but decision makers could only base their decisions on what they knew at the time. Nevertheless, the ferocity of the Japanese defenses at Saipan, Peleliu, and Leyte should have affected the assumption that taking any piece of real estate from the Japanese would be easy. The capture of Iwo Jima provided many lessons for the following assault on the Japanese island of Okinawa, principally to expect an extremely tough fight, and also to expect what an awful bloodbath any invasion of the Japanese home islands would be.

In the search for a justification for the loss of over 6,800 American lives for a tiny island, the rationale usually given was the 2,251 emergency landings made on Iwo Jima by B-29 Superfortresses, which in theory prevented over 20,000 airmen from ending up in the ocean. The reality is that most of those B-29s would probably have made it back to bases in the Marianas, but landing on Iwo Jima was a sensible precaution, since it was there. As it was, 414 B-29s were lost during the war, about 150 to Japanese fighters and anti-aircraft defenses, and the rest to operational causes, with the loss of over 2,600 airmen; it was a dangerous mission, especially in the early months. As it turned out, flying fighter escort missions from Iwo Jima generally proved to be impractical and unnecessary, especially since Japanese air opposition to the B-29s dropped off greatly after February 1945 due to shortages of pilots, aircraft, ammunition, and fuel. Even after the loss of Iwo Jima, the Japanese could still gain early warning of B-29 raids from Rota Island in the Marianas, which the U.S. never captured, although such early warning was of little use in identifying the likely targets of inbound raids, but then neither was early warning from Iwo Jima. The capture of Iwo Jima did prevent the Japanese from using it to strike B-29 bases in the Marianas, but even at the peak of such raids, B-29 losses were small, while almost all Japanese planes involved were lost.

In sum, the answer to whether taking Iwo Jima was “worth it” is probably “no.” However, that detracts nothing from the valor and sacrifice of those who took the island because it was their duty to do so. The U.S. Marine Corps Museum gives the Marine death toll on Iwo Jima as 5,931. Other accounts give a number of 6,800 are including about 880 U.S. Navy deaths, including Navy corpsmen, construction battalion, beach party, underwater demolition, ships and landing craft crewman, and pilots and aircrewmen (not including the air strikes on Japan). Approximately 1,900 U.S. Navy personnel were wounded in the Battle for Iwo Jima. The U.S. Marines paid a very dear price for the island, but the U.S. Navy paid a high price as well.